29 April 2020

Melbourne researchers at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute have revealed for the first time that males infected with the Toxoplasma parasite can impact their offspring’s brain health and behaviour.

Studying mice infected with the common parasite Toxoplasma, the team discovered that sperm of infected fathers carried an altered ‘epigenetic’ signature which impacted the brains of resulting offspring. Molecules in the sperm called ‘small RNA’ appeared to influence the offspring’s brain development and behaviour.

‘Intergenerational inheritance’ of similar epigenetic changes from men exposed to extreme trauma has been well documented. This latest research, published in Cell Reports, has raised the question of whether Toxoplasma infections – or even possibly other infections – in men before conception could impact the health of subsequent generations.

The research was led by Walter and Eliza Hall Institute researchers Dr Shiraz Tyebji and Associate Professor Chris Tonkin, in collaboration with Professor Anthony Hannan at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health.

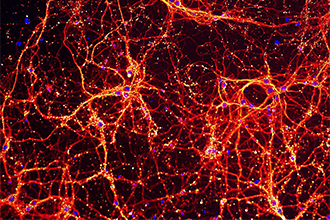

Neurons grown in the laboratory – image by Toxoplasma researchers Dr Shiraz Tyebji and Dr Simona Seizova

At a glance

- Melbourne researchers have revealed that mice conceived from sperm of males infected with the parasite Toxoplasma displayed changes in their brain function and behaviour.

- The study showed Toxoplasma infection in male mice caused changes in levels of ‘small RNA’ molecules contained in their sperm, potentially altering gene expression in the resulting offspring.

- As trauma in men can also cause epigenetic changes in sperm and has been associated with neuropsychiatric changes in their children and grandchildren, the research raises the possibility that men might also transmit changes associated with a Toxoplasma infection to their children.

Infectious inheritance

Toxoplasma is one of the world’s most common parasites, estimated to be carried by between 25 and 80 per cent of the global population. Toxoplasma infection can cause an initial mild illness in most people, however, pregnant women, babies and people with weakened immunity experience more severe infections.

Associate Professor Tonkin said people could carry the dormant Toxoplasma parasite for decades, and that this had been associated with the appearance of symptoms of mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“Toxoplasma infections have been shown to cause long-term epigenetic changes in a range of cells around our body. These are changes that do not alter the genetic sequence of DNA, but influence gene expression – that is, which genes are switched on or off,” he said.

“As other epigenetic changes in fathers – such as those caused by trauma or smoking – can influence their children, we decided to look at whether the effects of epigenetic changes caused by Toxoplasma infection could also be passed between generations.”

By studying male mice infected with Toxoplasma, the researchers were able to narrow their investigations down to the transmission of epigenetic information through sperm, Dr Tyebji said.

“We discovered that Toxoplasma infection alters levels of DNA-like molecules, called small RNA, that are carried by sperm,” he said. “These changes in small RNA levels affect gene expression, and so could potentially influence brain development and behaviour of offspring.

“We were stunned to see that even the next generation – the ‘grandchildren’ of the original infected male – displayed changes in their behaviour,” Dr Tyebji said.

Impacts for public health

Professor Hannan said this was the first time it had been shown that an infection in a male can result in epigenetic changes being transmitted to subsequent generations. “While our studies were in mice, it raises an important question about whether infections in human fathers before conception also impact their children,” he said.

“We normally think more about how infectious diseases in women affect the developing fetus, but perhaps certain infections in men could have long-term impacts on subsequent generations’ health.

“This is certainly something we are following up, both looking at what is happening in humans, as well as investigating infections other than Toxoplasma, including animal models of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes COVID-19,” Professor Hannan said.

Associate Professor Tonkin said the study was an outstanding example of how collaboration enhanced medical research. “We have combined more than a decade of research in my laboratory into Toxoplasma infections and their impact on brain development with the expertise Professor Hannan’s team has established in understanding the role of epigenetics in brain development and behaviour,” Associate Professor Tonkin said.

The research was supported by The David Winston Turner Endowment, the DHB Foundation (Equity Trustees), the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Victorian Government.

Read the full media release.