24 March 2020

In just a few short months, COVID-19 has completely changed the world.

From the initial novel Coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan to Europe becoming the new epicentre of infection, the world is at the mercy of a global pandemic. To further what is already a devastating global health emergency, chronic panic and misinformation have taken over many of the world’s most vibrant cities – resulting in toilet paper crises, empty supermarket shelves and an influx of sensationalised information on social media. As a result, it can be difficult to source scientifically sound, accurate information from the experts during this uncertain time.

At our virtual BioBreakfast event on Thursday 19th March 2020, BioMelbourne Network invited a key group of experts to discuss the topic “how to make a vaccine and why Victoria is so important”. The topic of vaccine development is universally significant, and understanding the time and resources required to develop a new vaccine is vital to this discussion. Given the rapid development of the COVID-19 situation, our discussion focused on current efforts to research the virus, vaccine candidates and the priorities needed downstream to effectively facilitate manufacturing upscale, clinical trials, regulatory tests and other essential processes. Given the vast amount of important information discussed at this event, we will be reporting it in several articles over the coming weeks. This initial summary focuses on Dr Rob Grenfell’s presentation.

Dr Rob Grenfell, Director of CSIRO’s Health and Biosecurity Business Unit, opened his talk by highlighting what a “different year” 2020 has already been. He walked us through the story of COVID-19 so far, highlighting the medical priorities of any infectious disease as vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics. Though this may sound straightforward, Dr Grenfell stresses the technical, financial and time implications of each option – in particular vaccine development. The development of a single vaccine requires “highly complex” research, development and manufacturing – costs between $350 million and $2.5 billion – and can take anywhere from 10-20 years to be available to the general public. The value and importance of diagnostics was also considered, as these “are essential” in testing the effectiveness of both vaccines and therapeutics. Diagnostics are also vital in mapping disease transmission and spread. Together with therapeutics, diagnostics and vaccines are all essential components of the current fight against our “enemy” – the causative virus of COVID-19.

So, we know that making a vaccine is a lengthy, expensive and arduous process – but how is one actually made? The vaccine development pathway is a relatively “tried and true” process involving basic research and development, optimisation, initial manufacturing, clinical development and GMP scale up and validation. However, this process can be very timely, with initial research and target identification phases taking between four and six years on average, and downstream clinical development taking five years at minimum. In terms of COVID-19, Dr Grenfell points out this is where the process gets “really exciting”. Due to the urgency of addressing the virus, things are moving much more quickly, with researchers suggesting a vaccine candidate could be determined in as little as “six months”.

How has this accelerated timeline become a possibility with COVID-19? Dr Grenfell stresses that researchers have been “really really busy”. From the moment the virus was first grown at the Doherty Institute, scientists have been collaborating with CSIRO to grow larger quantities of the virus, allowing further characterisation and testing. This includes analysing the genomic material of the virus and determining whether these building blocks vary between samples isolated from different patients in different areas. This is vital information in choosing a molecular target for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Another “important” piece of research Dr Grenfell notes is a study by researchers at the Doherty Institute which investigates what the virus is doing to a human’s immune system. This gives us insight into which type of vaccine might work best. Dr Grenfell’s team at CSIRO has also announced a “first-in-world” ferret model of COVID-19, which can be used for “analysing vaccines and vaccine capability”. Because of the sheer amount of technical work and expertise required, these preliminary studies on COVID-19 are essentially the equivalent of “three or four PhDs” completed in only weeks. The next phase will bring even more important work, including animal model vaccine trials – which if “all goes well”, will mean that vaccine candidates could be ready for initial human trials at “the end of June”. Steps following this would then be focused on manufacturing scale up, regulatory processes and clinical trials, which are long and complex undertakings in themselves. Industry involvement here is key. Dr Grenfell stresses that there are “incredible technical challenges and problems at an industrial scale”, and that the “discussions to actually do this” need to be occurring now.

Of course, this is but the tip of the iceberg. Across the globe, research teams are exploring multiple different vaccine candidates for COVID-19. However, from the research perspective alone, there are many difficulties involved in development of any vaccine candidate, let alone in a pandemic setting. These include challenges in the areas of workforce, infrastructure, technical knowledge, consumable supply, bureaucratic policies, priorities and funding. Dr Grenfell likens his limited workforce to “storming the beaches of Normandy” with “two little blow up rafts – it would be nice to have more troops”. Having “highly specialised” people to do this work is vital, and “preparedness” is a “very good investment” to ensure contingencies in times such as these. As Dr Grenfell states, creating a vaccine is “like putting a person on Mars” – the technical knowledge and infrastructure required to complete this research is expansive, and prioritising is difficult in an environment where you need the ability to “pivot fast”.

In pandemic situations, moving quickly is of the essence, however bureaucratic decisions and regulatory policies can inhibit fast progress. Access to biological samples and sharing materials nationally and globally is key component of vaccine research, however bringing materials into Australia can often take “two plus years”. In light of COVID-19, extraordinary measures need to be taken to share research resources both nationally and globally, with Dr Grenfell commenting that “something is wrong” with our system if we are unable to do this.

With many of these challenges, education is key. We are not all scientists, so how do we “tell people about complexity in a simple way?” Dr Rob Grenfell comments that even “inside many of our government departments and policy areas” there is a “lack of knowledge” regarding “how arduous and laborious it is to actually do this [research]”. Even beyond vaccine development and COVID-19, we need to be able to effectively communicate our research with the public, as well as to those that “support and fund us”.

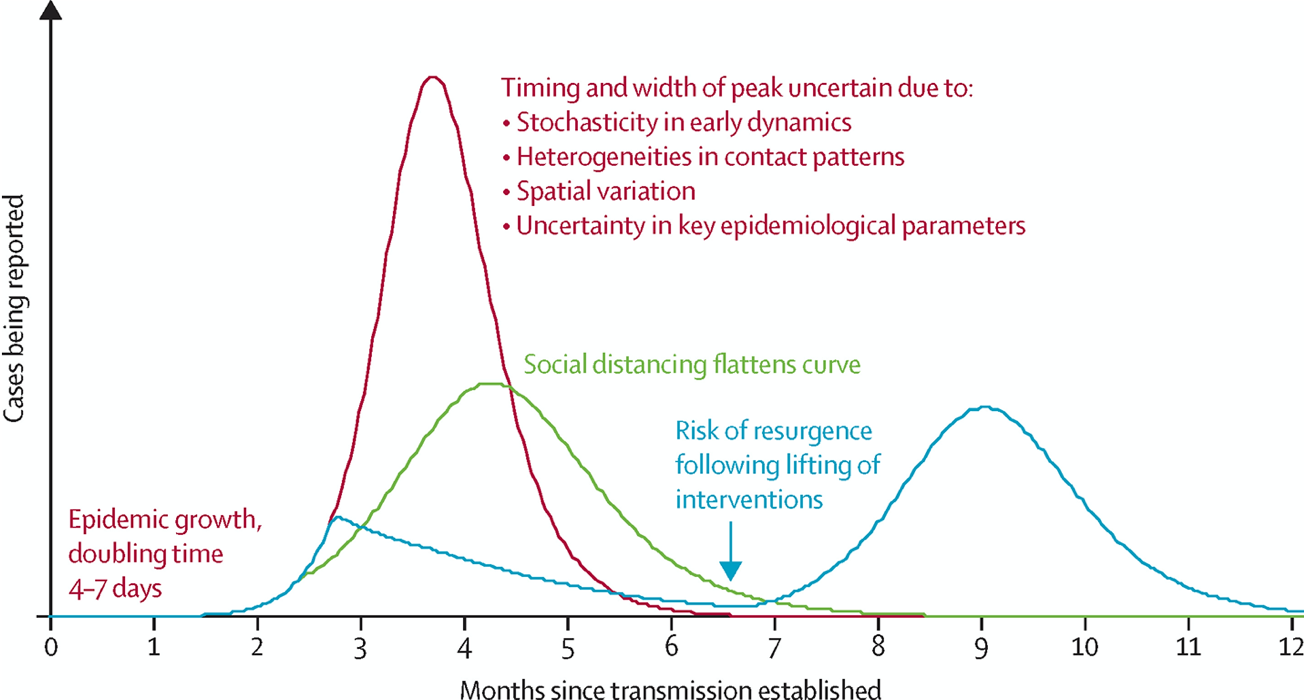

Illustrative simulations of a transmission model of COVID-19 A baseline simulation with case isolation only (red); a simulation with social distancing in place throughout theepidemic, flattening the curve (green), and a simulation with more effective social distancing in place for a limited period only, typically followed by a resurgent epidemic when social distancing is halted (blue). Anderson et al, The Lancet, 2020.

But where are we within this pandemic right now? Dr Grenfell alludes to the now infamous “flatten the curve” graph circulating the internet, pointing out a third peak that is often hidden1. This additional peak refers to potential resurgence of COVID-19 infections, which may occur if measures such as social distancing, increased hygiene and lockdowns are lifted too soon1.The “mythical figure” where the green line plateaus (representing “flattening the curve”) indicates the maximal peak of reported infections we can reach to “make sure our hospitals can still cope”. Dr Grenfell and colleagues predict that sometime in “May, June” we will be in the “disaster zone…with regards to our healthcare system”. The good news? If we get this right, hospitals will be “coping” – but they will not be operating at “optimum levels”.

The COVID-19 virus is incredibly “cunning”, and to target this enemy we need to continue working. Dr Grenfell lists his priorities as “drugs”, “diagnostics” and “vaccine work”, and beyond the science we need “consistent messages on what’s right and wrong”. Dr Grenfell states that as a community, we are “denying that we’re actually in the middle of a very serious event” and we need to remember that “2020 is a different year”.

Looking to the future, what can we do? On a national level, it’s “no different than a cybersecurity response”. We need better infrastructure to prevent, detect, respond and recover, with Dr Grenfell excited to mention that we’re now starting to “plan the recovery” phase. However, Dr Grenfell stresses that we need a “platform centrally directed under existing frameworks” to “provide mechanisms necessary for national infrastructure and workforce effectiveness regarding the prevention of and efficient response to biothreats”. This means facilitating access to scientific knowledge and technical expertise, proactive, responsible action from governments and engagement with and assistance for industry, particularly for manufacturing capabilities, all delivered in a structured way.

To close his presentation, Dr Grenfell provided some optimism, reminding our audience that Victoria has “all the elements” to create a COVID-19 vaccine. Victoria has directed a vast amount of cancer and disease screening and has “invented so many things”, including the National Immunisation Program which has become one of the “envies of the developed world”. Here in Victoria, we have the “key assets to actually respond to a global crisis” and one of the things we need to do as a state is “power” a “coordinated national approach” to combat COVID-19.

1: Anderson, R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg, D. & Hollingsworth, T.D (2020). How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet, 395, 931-934, DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5

We would like to thank the State Government of Victoria through the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions for their continued support of our BioBreakfast series.